Ginger Spice Chai: An Equal Place on Bookshelves

We all want children to be safe. So why do some want those children to have less resources and more fears?

Hello, everyone!

It’s been a while since I’ve prepared an Afternoon Tea for you all! I’ve been busy working and trying to make some cool new stuff, so a lot of drafts went incomplete, but given some current events here in my twin-island home, I’ve been pressed to share a new issue with you all.

If you're new (or, let's be honest, if you've been wondering where the Afternoon Tea has been for a couple months), a reminder that you can support this and my other writing via Ko-Fi so the Tea can keep flowing:

But without further ado, here’s a cup:

Fear of a Rainbow Cape

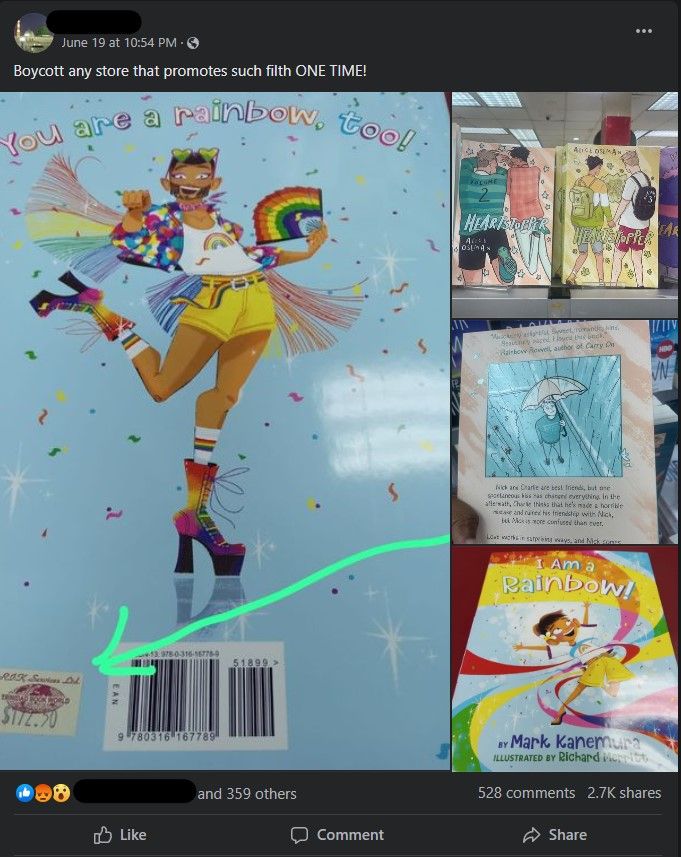

At 10:54 p.m. on June 19th, 2023—too late in the day to make sense and very early in the night for bacchanal—a man shared a series of photos on Facebook. The photos were of that awful thing that all parents dread, that thing that makes their hearts skip a beat in the dead of night when nothing can hear you cry out in agony:

a book.

[This newsletter includes heavy discussion of child abuse, including child sexual abuse, and homophobia and transphobia.]

Frustrated that a then-unnamed branch of local bookstore RIK Services Ltd. had copies of Mark Kanemura’s I Am A Rainbow and Alice Oseman’s Heartstopper on store shelves, they and several other users decided to express their distaste publicly, even calling for the store to be boycotted. Within a matter of hours, those posts would be shared and commented upon hundreds of times, breaking through the otherwise fickle Trini social media consciousness.

The rallying cry among many who saw it seemed to be the same: this is a disgusting attempt to sexualise our children, to groom them, and that it must not only be challenged, but banned.

It grew in intensity almost immediately. Some parents insisted that it being in the bookstore was a tacit endorsement, specifically an endorsement of queer sex, and that the book should pull it from shelves or be boycotted for their role in taking advantage of children. That led RIK to respond, first with strongly coded jest, then with a serious confirmation that they do not discriminate. It barely took two days for folks to then insist these books were also on the Ministry of Education curriculum (because, I guess, when a community of adults only enter bookstores when it’s schoolbooks season, bookstores only sell schoolbooks), leading the Ministry to officially respond.

It even got as far as the Inter-Religious Organisation of Trinidad and Tobago (an organisation already mired in drama regarding the safety of children when they unsuccessfully opposed updating legislation to outlaw child marriage in 2016), with its present president publicly insisting that LGBTQ+ persons should be segregated from public life. Then the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Port of Spain Jason Gordon, who drew Christian ire just a few months ago for defending the decriminalisation of homosexuality (while still insisting it is a sin for some reason), went out of his way to challenge the misinformation regarding the books… while still insisting that the Concordat of 1960, a historical agreement between the boards of several denominational schools and the then-Ministry of Education, maintains control over what books are introduced into said schools, which has been an issue since the Catholic Education Board and other religious leaders stood against comprehensive sex education in schools.

So, to be sure: the notion that a bookstore sells books has reawakened decades-old absurd fears about the safety of children from communities that have politically defended child marriage, calls to defend parental rights of refusal of the very kinds of education designed and shown to reduce instances of sexual violence, and publicly accuse an entire marginalised community of sexually grooming other people’s children when the vast majority of sexual and physical abuse of children in the region takes place in the home by immediate adult relatives. Not to mention the obvious instances of people speaking of the allegedly godlessness of the government (yea, verily, the people for whom the very book brouhaha was late news), expressing frustration about the island is being corrupted by ‘American slackness’ while paradoxically reposting propaganda videos from the Daily Wire, actually calling for violence against queer people, and even intimidating bookstore employees.

Now, it is at this point that a lot of things come very easily. It is easy to say that we’re just doomed, that the hegemony of religious political power will keep us in a rut of incomplete sexual self-awareness and security until every child on the island has suffered. It is easy to just throw one’s hands up and say, ‘well, I guess we just like it so’, and let our bitterness at the parents happy to leave the system as it is consume us. It is easy to be too angry to move.

Or at least I have been too angry to move.

A regular litmus test I try to apply in situations like this (and less significant situations besides) is to remind adults that they were once children. This isn’t necessarily an insistence that children are self-governing, but that they do have feelings, opinions, and desires; just because they can’t rationalise in the same way as an adult doesn’t mean they can’t at all, or that they can’t learn the skills to or that we mustn’t teach them. The assumption otherwise is the assumption that a child is not a person, but a parent’s property, without significant emotion or thought whatsoever—and that is the mentality that leads to a great deal of abuse and neglect.

Why is it important to remember that we were once children? Because it’s also important to remember how we felt when people valued our perspective enough to consider us stakeholders in our own feelings and our own future… and how we felt when someone we loved and trusted denied us that stake. Even for something as petty as what we eat and when, being at least considered human enough to be reasoned with is better than, in a lot of Caribbean circumstances, being spoken down to or, worse, being struck just for expressing the want at all. I’m sure many Trinis have seen it, and I can only guess at whether anyone has seen the same elsewhere: that moment when a child of any age says in public that they want something, they feel something, they don’t like something, and their parent either rolls their eyes in an anxious sigh, just tells the kid to behave without further explanation, or just plain hits them. In Trinidad, it does happen for as little as wanting a pack of potato chips at five in the afternoon when your mother just stopped at the parlour for some sugar.

What does that have to do with this, dawg? I’m getting there.

I am asking this because it’s also important to express grace to everyone involved in this cycle of fear and distrust. Grace to queer Trinis who are tired of suddenly being lumped into a theory of harm that statistically does not include them. Grace to parents who may be rightfully afraid for the children they truly love, but are deliberately being fed propaganda by people who want them left out of real talks about children’s sexual safety for political ends. Grace to educational spaces like schools, libraries, and bookstores who truly want to make more information available to all but are cut off at the heels at every turn by people who politically benefit from that ignorance.

But a lot of that grace has to go to children. Because they’re being used as puppets in a war over a book many of them probably didn’t even notice and most of them can’t even buy (hell, I’m a big man making my own money, and I can’t buy it right now—a hundred and eighty dollars TT for a picture book? But I can’t knock the hustle).

But also children deserve that grace because their lives are at stake.

It is very easy to pick the low-hanging fruit of challenging an ignorant parent to consider whether they would truly love their child still if they discovered they were queer, or to rightfully indict the Christian establishment of its own harms against children in this region and elsewhere, but even that is simply continuing to use children as a shield instead of actually shielding children. The more useful framework, to me, is to draw attention to what those young people will end up learning, and what they will end up continuing not to know:

As a result of this rhetoric, many kids will end up learning that there is a community of people synonymous with harm even without committing any, and that it is socially acceptable to shun or even hurt them, and that you can tell it even in other children, making it a prime weapon to wield against them whenever they behave in any way abnormal, or worse, just to verbally abuse them, all while none of them know enough to defend themselves against real harm. You already know it happens all the time.

Worse, it deliberately disables and destabilises the processes designed to actually help children, not only from the bullying taking place in class, but from the potential abuse taking place outside of its walls. Adults who are harming their own children—either out of genuine malice or out of the misguided tactics of parental discipline and control that lingered in our family trees as cycles of trauma since our grandparents were children—now get to use parental rights as a smokescreen to hide their own actions, all while they cast the blame toward a community that is rarely, if ever, even interacting with their children at the same scale. When a teacher, a social worker, a guidance counselor, or even another parent or child notices something amiss, that same parent gets to say they’re one of you when they tell every other concerned party to mind their business. Adults who harm children are so very eager to tell them that there are people they mustn't trust more than them, and questions they mustn't ask anyone but them, specifically in order to control how little that child is allowed to think about their pain, and how much of it others are allowed to see. You already know it happens all the time.

And in all of those instances, that child only gets to see how unhelpful and unhealthy this is. It gives their bullies ammunition to harass and even attack them, it leaves them vulnerable to violence just until the moment they decide to seek the education out on their own tenuous and frightening terms, and it reveals to them that no adult actually trusts them. Not enough to ask them how they feel. Not enough to be capable of learning or reasoning. Not enough to be forewarned and therefore forearmed against trauma. And when the trauma comes, they will feel isolated and ashamed, and when the parents around them ask why they didn’t know, why no one was talking about it…

… well, do you remember, or can you imagine, being a child in a moment like that? What that felt like?

Did you like that feeling?

Wanting to keep children safe means wanting to have every tool available in that security. We can’t keep saying ‘it takes a village to raise a child’ and then keep the village out of the spaces where real harm is happening. We can’t keep letting people tell the parents of our nation’s children that because of who someone is, they are untrustworthy as comrades in the work to build a better society, at precisely the moment when children’s lives are more at stake than ever. We can’t keep saying we want and trust children to reach out to us and tell us when they’re in danger and then continue literally denying them the words to do so. And we definitely can’t keep doing so under the misgiven assumption that there is a community whose very identity is a threat to decent society without ever considering whether we’re saying that we don’t love our own children, or encouraging them to deny others dignity in turn.

We hadda do better than that.

And a good place to start is by letting go of fear and propaganda and actually being willing to address actual violence against children at its real roots, and by letting go of homophobia that not only separates us from our neighbours but may even alienate us from our own children in turn. And a good place to start with that is by engaging deeply with art that teaches children about themselves and gives adults a multitude of examples of the wealth of people that exist in the world, so that everyone is on (hopefully) the same level of empathy, awareness, and kindness necessary to share space in a tolerant society.

Ironically, Kanemura’s book has one of those keys. I Am A Rainbow is all about a young Mark learning self-confidence and becoming resistant to harassment and negativity precisely because his family embraces his curiosity and brightness, represented by his parents gifting him a rainbow cape. (It’s very much giving Joseph and his coat of many colours.) It’s the story of a kid gaining friends, enjoying the safety and comfort of open and trusting parents, and learning to be resilient in the face of uncertainty.

Would that every child—and every parent—would read and see the value of such a story.

Tasting Notes

There are many good places to begin dissecting the panic around LGBTQ+ person’s exaggerated threat to children, and many of them can either be incredibly dense or overwhelmingly intense. Here are but two potentially accessible and palatable videos with which to challenge this ignorance:

ethan is online’s ‘The “Groomer” Narrative is a Lie’ does a great job of breaking down the historical origins of this narrative in the United States, how it is historically constructed, and useful statistics regarding the actual people posing a statistical risk to minors in the American context. The actual study cited, the publicly available Williams Institute survey of LGBTQ People on Sex Offender Registries in the US, makes it disturbingly obvious that the vast majority of people committing these harms (80% of the survey) are cisheterosexual men, and that said straight men are more likely to harm a family member, more likely to be given no jail time, more likely to receive lesser sentences when they do see jail, and less likely to suffer verbal abuse or physical assault, and that those imprisonment and harassment outcomes that LGBTQ+ offenders experience are markedly worse if you are a person of colour or a woman. If we really cared about defending all children, or even simply despising all abusers, this would not be the case. And yet.

(Of note, for any Caribbean readers around: the Children’s Authority of Trinidad and Tobago’s reports do not include statistics broken down very deeply by the demographics of perpetrators relative to their victims, but as of the latest statistics the comparison very obviously bears out: the vast majority of perpetrators of sexual violence are cishet males, and the vast majority of victims are young girls, and children are more likely to be victimised by a close relative, especially a parent.)

Much more powerful (and by comparison quite a bit longer) is Caelan Conrad & Little Hoot’s ‘What Is A Groomer?’, a deeper dive into some of the similar constructions of this panic, going even further to the Satanic Panic of the 70s and 80s, even more strongly clarifying the connection between this rhetoric and the direct goal of violence toward marginalised communities, the consequences these actions have on young people actually suffering abuse, and what we can do to respond to it proactively.

Of course, the hard part is that this is still very accessible for someone who is aware that this is an issue and wants to confront it, but it can be difficult to broach this conversation with someone you love who has given way to this ideology. Sadly, this can be a hard place to give tools for that: no one has yet made a YouTube video targeted to worried parents about this issue.

At the very least, this is what I offer: when talking to those you love about this issue, specify first and foremost that you both have common ground on the issue of the safety of young people.

Clarify that this rhetoric doesn’t make children safe.

Clarify, as Ethan does, that children are far more likely to be harmed by a relative; do so without implicating them as individuals or making them feel accused.

Clarify, as Caelan does, that children need comprehensive sex education resources in schools specifically because they need the language to be able to see harm and describe it to trusted adults in situations where caring parents may not be present, without feeling the shame or rejection that would prevent them from sharing. Do so in order to reiterate that having more trusted voices looking out for children makes their world safer and more open.

Clarify, as many people have, that there are so many parts of our mainstream culture (in the US as in Trinidad as in elsewhere) that normalise sexualising children in a heterosexual context, like the ways we teach boys to approach girls, or the way we describe young women in spaces where they are meant to feel safe, in ways that have never been the case in mainstream queer community; use that as a space to discuss why queer people are the subject of social scrutiny despite this. Do so without implicating them in that sexualisation, but in order to ask deeply why those sexualisations are normal where a lack thereof still makes queer people abnormal.

Clarify, as many people have, that their child may end up being queer later in their life without any trauma being the cause whatsoever, but may learn from these discussions that the people they love do not trust them or find them worthy of affection.

Clarify, as many people have, that even if they never become queer, they will have learned from the people around them that there are people who are not trustworthy or worthy of affection, and will be motivated to shun, disrespect, or even abuse them, safe in the knowledge that there will be no repercussion for such. Clarify that even other straight people will become victims of such violence, including young people, even as a result of simply being in proximity of a primary target of that distrust.

Clarify that at all these stages, more people become unsafe, and there is no excuse for that.

A reminder (especially during bill-paying season) that this newsletter, as well as the rest of my writing and game design work, thrives with your support. My Patreon is where you can find snippets of new TTRPG projects, exclusive writing drafts, and more:

Today's Tunes

In lighter news: Little Simz dropped a banger of a video the other day.

I know the streets'll love it like I brought Mike Skinner...

I am still slowly working my way through NO THANK YOU—I didn’t even know Simz had a new thing out until I saw this video, and sadly, writing time means also writing playlist time, so I haven’t had the mental space to truly sit with an album like I should—but when this video dropped, I had to stop what I was doing. It’s grand. It’s the perfect visual vibe for the bombast that it opens with in that brass (aside: dat brass dawg! That alone could start my day proper. If I could set a Spotify track as my alarm, I already would’ve).

To be sure, what I’ve heard of the album is equally hype, and par for the course for the rapper’s talent. I can’t wait to properly dig in (once I’m not working on this short story WIP, and the backup short story WIP, and the novella WIP, and, and, and…)

Anyway, here’s this sampler of the album, the visuals of which are also wild as hell:

The Leaves

So that's all for today!

A reminder that you can help keep this newsletter and the rest of my work afloat by supporting me on Patreon, buying me a coffee on Ko-fi or sending a donation via PayPal, or by buying one of my small game projects over on Itch!

Also of note: The Queer Games Bundle 2023 is live on Itch! As we're in the last few days of Pride, consider supporting the bundle—over 400 works of queer art, including visual novels, tabletop RPGs, books, and art, for only US$60! (There's even a budget version of the bundle at a Pay-What-You-Can scale between US$10-20—much less than the cost of a picture book, apparently!) Given the content of today's newsletter, a good way to support queer people is to actually pay them for their stories.

Also also: it's been so long since we shared some tea that I never got to mention that I have a story published in Sunday Morning Transport a few months ago! 'The Officer In Your Heart' is about the inherent peculiarity of the body, about queer yearning and queer rage, about the tension of maintaining radical community in the midst of fear and infighting, and also about giant robots fighting giant aliens. Very apropos for the moment, no?

But before I go, some questions:

- What is the last book you’ve bought from the bookstore? (It doesn’t matter if you’re not reading it yet—I can’t judge you.)

- What do you wish you could tell your younger self about how to survive the hard times of youth?

And while we’re on the topic of young people having to learn their own resiliency in the face of adults throwing them headlong into trauma, here’s this impeccable Demon Slayer TikTok from @nicquemarina, who you should definitely be following on all platforms.

Until next time, I hope you enjoyed the tea!